Under the headlines, “What the Arrival of A.I.-Fabricated Video Means for Us,” the New York Times announced yesterday, “Welcome to the era of fakery. The widespread use of instant video generators like Sora will bring an end to visuals as proof.”

“This month, OpenAI, the maker of the popular ChatGPT chatbot,” the article by Brian X. Chen begins, “graced the internet with a technology that most of us probably weren’t ready for. The company released an app called Sora, which lets users instantly generate realistic-looking videos with artificial intelligence by typing a simple description, such as “police bodycam footage of a dog being arrested for stealing rib-eye at Costco.”

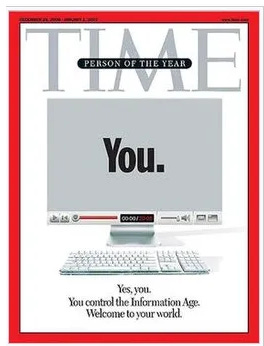

The Times published an image (above) at the top of the article that seemed to resemble a tombstone. And the image (by Sisi Yu) bookended, at least in my mind, Time magazine’s 2006 “Person of the Year” cover, “You.,” that showed a computer with a mirror-like rectangle in which readers could visualize themselves.

Both the Times article and the Time cover reference consumer entitlement and corporate greed suffused with outright deceit. The magazine’s cover refrain that “Yes, you. You control the Information Age. Welcome to your world,” is chillingly Orwellian, asserting the opposite of what was actually happening. If people in fact controlled the “Information Age,” as Time asserted, it would not now be more aptly named the “Misinformation Age.” We were, in retrospect, victimized while made to think that we were in control, “users” rather than “tech bros.”

Chen, the author of the Times article, writes that “The arrival of Sora, along with similar A.I.-powered video generators released by Meta and Google this year, has major implications. The tech could represent the end of visual fact — the idea that video could serve as an objective record of reality — as we know it. Society as a whole will have to treat videos with as much skepticism as people already do words.” This, of course, follows the undermining of photographic credibility by software such as Photoshop and AI-generated imagery. The short-lived hope had been that at least video testimony, being a more difficult technology to manipulate, would survive.

Chen concludes: “But any advice on how to spot an A.I.-generated video is destined to be short-lived because the technology is rapidly improving, said Hany Farid, a professor of computer science at the University of California, Berkeley, and a founder of GetReal Security, a company that verifies the authenticity of digital content.

“‘Social media is a complete dumpster,’ said Dr. Farid, adding that one of the surest ways to avoid fake videos is to stop using apps like TikTok, Instagram and Snapchat.”

Given the glaring shortcomings of conventional media, giving up social media with its multiple, more personal perspectives seems like a major step backwards. But Farid is right that social media’s usefulness has just taken a major hit. For those interested in the voices of those with less power—people in Gaza, for example, or those being arrested and deported from the streets of the United States—the demolition of credibility that these video generators bring with them is breathtaking, rendering nearly all imagery immediately suspect. How will one be able to differentiate the real from the fake? Not everyone has the time to check and counter-check sources. Will it be still possible for people to engage with the other, to care?

What I find shocking, given the various articles that render essentially the same verdict on the end of “visual fact,” as Chen put it, is the lack of response from governments, tech companies, journalistic and legal organizations, historians, archivists, educators, curators, and the rest of us. Isn’t it time to do something?

Why are organizations not urgently sponsoring wide-ranging forums on what to do about the collapse of credible visuals, bringing in people from various disciplines? There is not going to be an overall technical solution, at least not in the near future, particularly given that tech companies have been mostly coldly indifferent to the societal and personal impact of their products.

Shouldn’t there be legal and professional constraints with penalties attached for the serious deceptions that will now emerge in even greater numbers? Or is this collapse into chaos being viewed as inevitable or even favorable, particularly by those with extremist or autocratic aspirations?

Certainly, there are no easy answers. But that should not stop us from trying.

Who will lead the way?

Please consider subscribing, including as a paid subscriber. The issues are important enough to help support the discussion.

The decisive moment was everything, in photography. Perhaps we are the last to really appreciate what that was.

Here’s an initiative from book publishing that intersects with the ‘Writing With Light’ campaign: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2025/oct/15/books-by-people-for-people-publishers-launch-certification-human-written-ai