“For many Ukrainians, images of the Russian war have become more than just photographs: each one is an embodiment of the particular knowledge we all carry within us now. At least I can speak for myself,” writes cultural critic Kateryna Iakovlenko in e-flux. “These images of conflict remain horrific; they evoke various strong feelings that manifest as ants crawling on my skin, a panic attack, anger, or a desire to leave the apartment and lock up my own body until it survives the grief that the photographs produce. I want to mark my body ‘sensitive,’ as the photographs themselves are sometimes labeled online. I want to close my whole self off from others’ sympathetic or apathetic views.”

But from the outside it is different. “Google image search results about the war show mostly professional images taken by photojournalists for their agencies…. This presents a very different picture of the war than the one I will remember. Media corporations represent the war diplomatically. The photographs are made professionally and with a symbolic distance from the subject.” She decries the absence of “so-called poor images” with their “lack of distance,” preferring those “taken hastily on a phone without retouching.” Nor are there in the Google search results “drone visuals, thermal imaging, or phone images of horrors.”

I am in agreement. It is often the rawest imagery, made by soldiers in Abu Ghraib while torturing Iraqi prisoners, a passerby in Teheran depicting philosophy student Neda Agha-Soltan as she died on the sidewalk during a presidential election protest, a teen-ager making a video of the police in Minneapolis murdering George Floyd, that pierces the typical media restraint and make it more difficult for a viewer to resume the lives they once lived.

Last week I moderated a discussion among four photographers working in Ukraine, three of them Ukrainian (it was sponsored by the ICP Living Room, an initiative directed by Alexey Yurenev). At one point, I asked them to differentiate between the work they did for mainstream publications and the imagery that they published on social media. The difference, they said, echoing Iakovlenko’s argument, was that on social media one could be more personal and emotional.

Then, one might ask more broadly, is there also room for a perspective that melds the personal and emotional but does it slowly and meditatively, with intuition and ambiguity, allowing for subtleties that might emerge only over time? Might we also task professional photographers with asking what happens when these horrors, concretized in picture after picture, are not as visible but instead slip underneath a person’s skin and lodge there?

The photography of war can then explore how a person lives within an unremitting aura of violence that, even after the war ends, they will still carry within them. Trauma cannot simply be asked to leave.

Or, as William Carlos Williams famously put it, “It is difficult to get the news from poems yet men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there.”

Ira Lupu is a Ukrainian photographer, living between New York and Ukraine, who was on the panel discussion that I cited above. I have worked with her previously in many capacities, including as co-curator of exhibitions on the conflict in Ukraine; she has also been my teaching assistant and student.

The photographs and accompanying narratives published here are by Lupu, from a series that she did called Spovid, or Confession, which is part of a larger collaborative group project, “Beyond the Silence”:

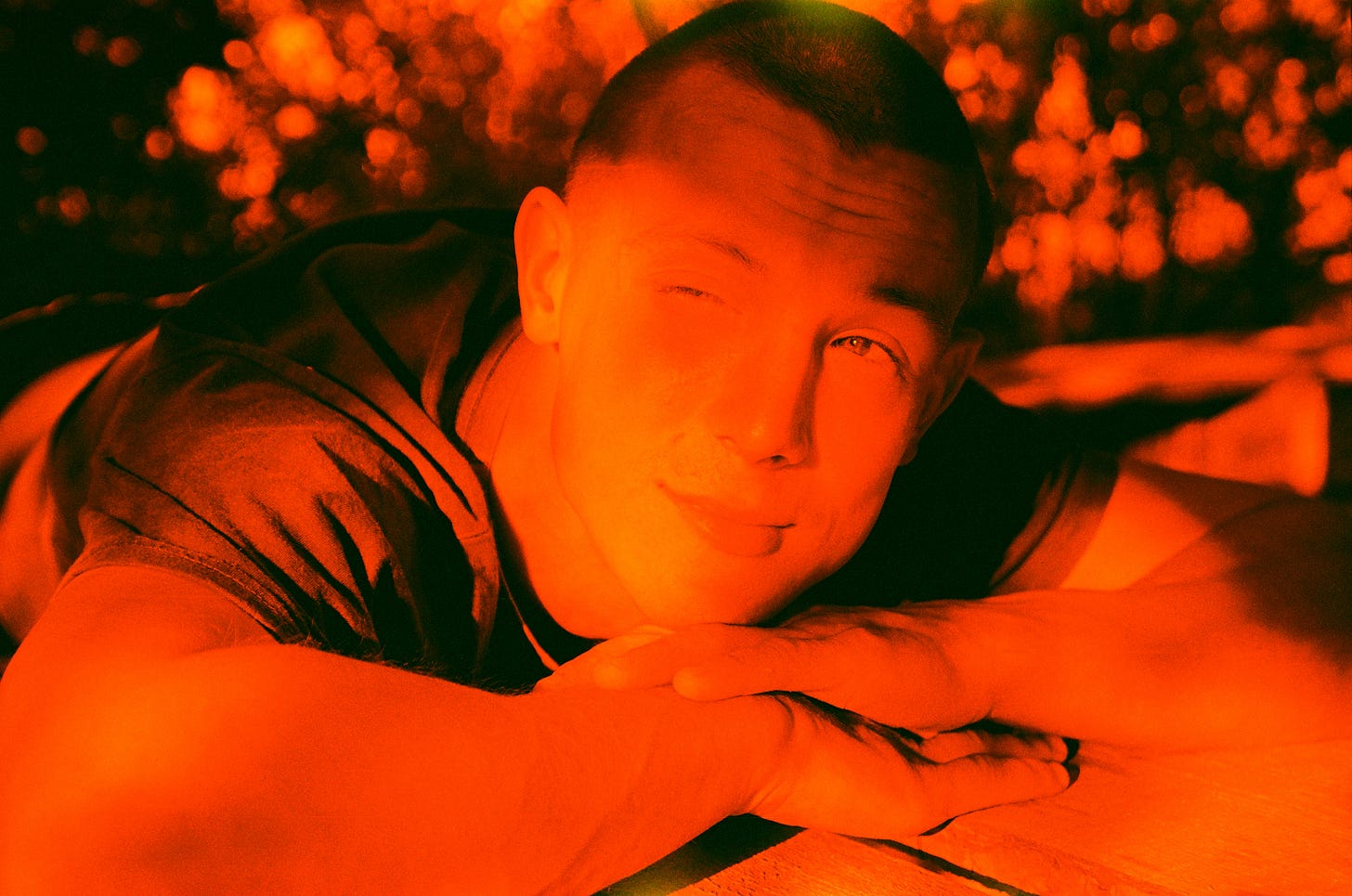

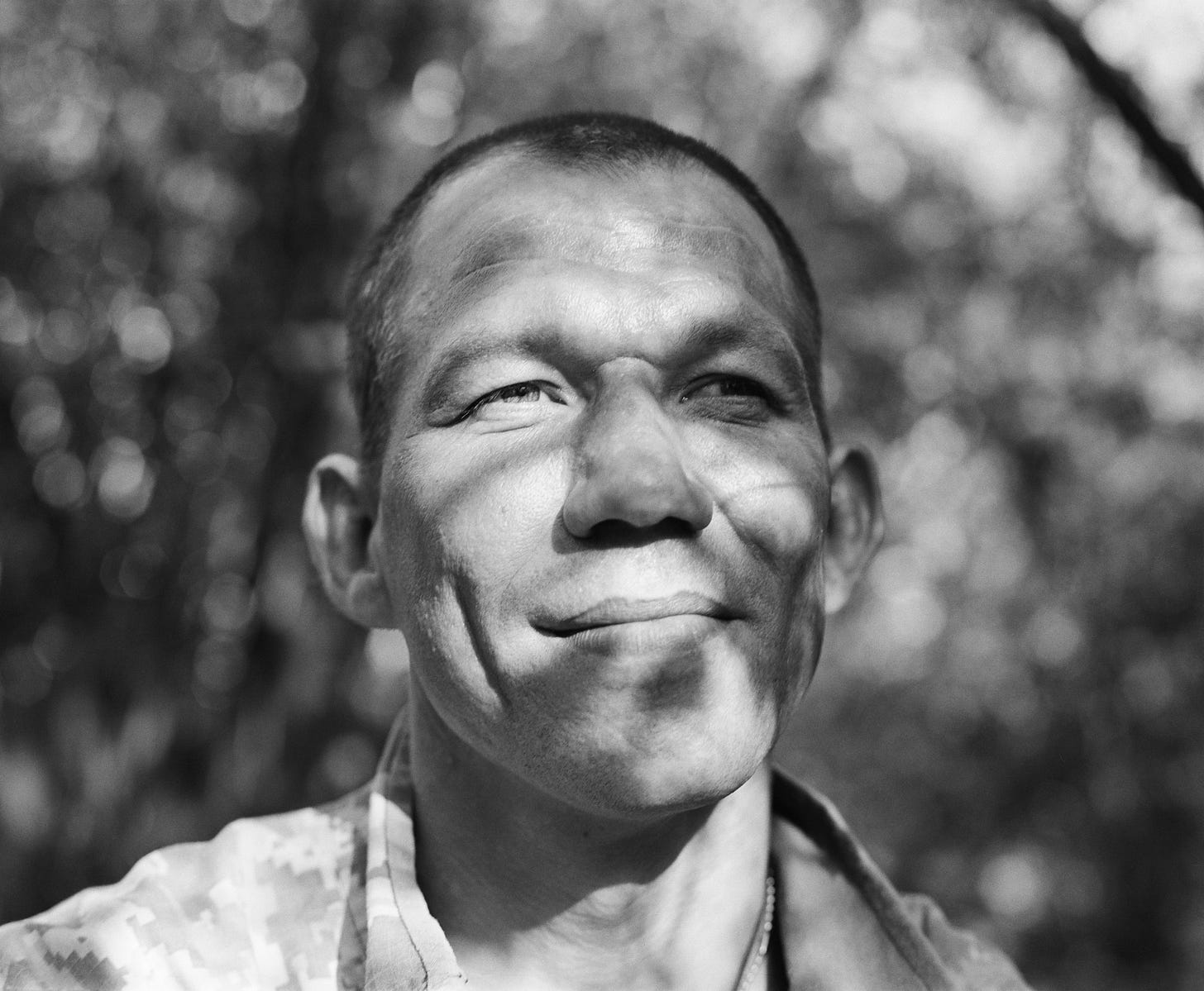

“These are the fighters of the First Separate Assault Brigade—former convicts released on parole after choosing to go to the frontline,” she writes. “I photographed them at a training camp in the pre-frontline zone of Zaporizhzhia region, on their last day off before their first shturm—a Ukrainian term for a ground assault mission.”

“At first, they were gruff, insisting they wouldn’t share anything personal. But within minutes, most began to open up. Some confessed their stories, some cried—it may have been the first time they had ever truly spoken about themselves. By the end, as a gesture of recognition, they brought me chocolate and energy drinks, a prized currency among active servicemen.

“As the sun set, we rushed to the field for a group shot. Now at ease—both with me and in front of the camera—the former prisoners played and laughed like little boys.”

“Call sign Little Boxer. He asked me to send the photographs to his mom so he scribbled her email in my notebook.”

“Student—the one with the turtle tattoo on his torso—was the first to be killed in action.

“The commander told me that Lyam, who hugs Student in an earlier photograph, was deeply shaken by his loss. He would never admit it, but he became more cruel on a battlefield.

“The second was Mongol—the most seasoned among them, yet always energetic and optimistic. And an Aquarius, like me. A veteran of the Donbas war that started in 2014, he had been serving a prison sentence for attempting to attack someone with a knife in a restaurant. ‘I was drunk,’ he told me that evening as the sun set. ‘And I started hallucinating that the room was full of Russian soldiers.’

“One of my personal symbols of the war became Chasik, a zealous, caricature-like thief who had only eight months left to serve in prison. But, as he put it, ‘To hell with living like that.’ He was from Chasiv Yar—another frontline city now reduced to rubble. He barely spoke to his family but dreamed of avenging their fate—and going on a round-the-world trip with them. He became a leader in the company.

“Chasik burned alive from a tank shot. A hero in his dedication, even if a villain.”

“On the evening of July 4, the Armed Forces of Ukraine officially reported a possible provocation being prepared by Russian forces at Europe’s largest Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant that they occupied in the beginning of full-scale invasion. According to operational information, foreign objects resembling explosive devices had been placed on the outer roof of the third and fourth power units. Satellite images later confirmed the appearance of new objects on the roof.

“Across the country, fear of a second Chernobyl was palpable. Pharmacies quickly sold out of iodine pills, believed to offer some protection against radiation.

“Meanwhile, on the banks of the Dnipro River in central Zaporizhzhia, just a two-hour drive from the plant, teenage athletes played beach volleyball. After the game, they rushed, laughing, into the water.

“In the distance, the rumble of frontline artillery echoed. Due to the ecocide caused by the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam, the river had receded, exposing mudflats sprinkled with unexploded WWII-era shells. Later that day, a policeman ordered us to leave the beach after one such shell was discovered.”

“I traveled to the frontline part of Kherson Oblast passing devastated villages along the way to Snihurivka, its name on the entrance sign still painted over.”

“My friend, an internally displaced refugee from Mykolayiv, now lives in Kyiv. Most Kyivans have grown somewhat accustomed to the daily drone strikes, but not her. When an air raid alert sounds, she stays up all night, anxious, while I keep sleeping.

“‘It’s because I’m still in touch with reality, and you guys aren’t anymore,’ she says. I can’t disagree.”

In her eloquent essay quoted above, entitled “Exactly That Body: Images Against Oppression,” Iakovlenko asks the central question, as many of us do: “What can an image do in the face of such ongoing atrocities?” She also quotes Sontag from her seminal book, Regarding the Pain of Others: “In contrast to a written account—which, depending on its complexity of thought, reference, and vocabulary, is pitched at a larger or smaller readership—a photograph has only one language and is destined potentially for all.”

I do not completely agree with Sontag. Photography can also have a “complexity of thought, reference, and vocabulary,” in large part due to the sophistication, intuitiveness, and experience of the photographer. And a photograph has more than one language: there are, for example, “poor images” (Hito Steyerl’s term referenced above), the more “diplomatic” ones of media corporations, and then photographs such as Ira Lupu’s.

We should be using all of these languages, and more, to confront and resist the growing chaos and obscene cruelty of our age.

Please consider becoming a paid subscriber. It would be much appreciated.