Melting ICE

Continuing to believe our eyes and ears.

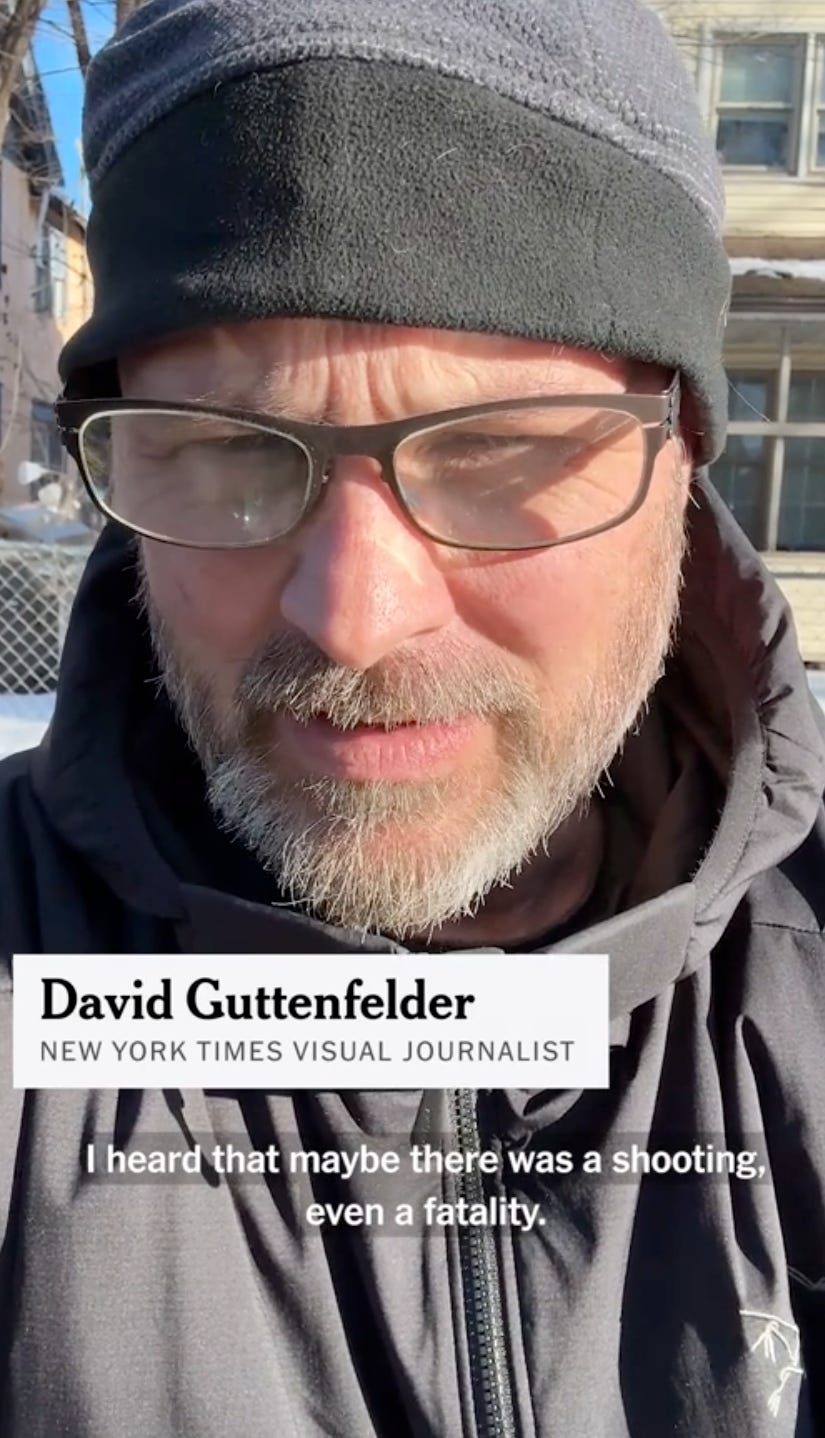

Among the work done by various photographers in Minneapolis, the photographs and video by David Guttenfelder stand out, describing the events around him as his native city is invaded by swarms of ICE agents. In one of his photographs (below) he narrates, in a video published online, how the man in the snow is trying to recover after his eyes have been sprayed by a chemical, while another near him is being wrestled to the ground by an ICE agent and the second agent has just been hit by a snowball. It is one of many cataclysmic scenes that he depicts. He also recounts how the militarized ICE agents there are dressed similarly to soldiers in the war zones that he has recently been covering in Ukraine and the Middle East.

Looking down as he speaks into a microphone, Guttenfelder’s tone is somber, almost elegiac, as if reciting a prose poem in which he talks of witnessing numerous scenes of violence and anguish. His is a Walt Whitman-like perspective, much like the 19th-century poet’s encounter with the American Civil War when he worked at a hospital caring for the grievously wounded and would write empathetically of suffering and healing, democracy and ideals, envisioning his poems in a symbiotic relationship with the larger society. (Whitman wrote in the preface to the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass: “The proof of a poet is that his country absorbs him as affectionately as he has absorbed it.”)

But the imagery that marked a turning point in a larger understanding of ICE and its methods were the several bystander videos that recorded the seconds leading up to the shocking murder of Renee Good as she tried to drive away from the ICE agents who surrounded her car, augmented later by another that was released which was made, stunningly, by the ICE agent who then shot her. It was not just the imagery that captivated viewers, but the sounds of bystanders yelling and screaming, as well as the three sharp bangs as Jonathan Ross fired at the car and killed her. It was these sounds that provided the context for what was happening, that affirmed the authenticity of the act of witnessing, as well as the horror of it. And the narratives provided by the videos allowed viewers to follow the sequence of events, to compare each with the others, and then allowed them to make up their own minds as to what had happened. This latter point is crucial.

Masses of people concluded that the 37-year-old mother of three was not attacking anyone but simply trying to leave the scene in her car, making the shooting entirely unwarranted and amounting to murder; she was a threat to no one. As high-placed members of the US government denied the evidence of these videos and instead blamed the victim as some kind of “domestic terrorist” there were many, including the governor of Minnesota, who quoted from George Orwell’s 1984: “The party told you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears. It was their final, most essential command.”

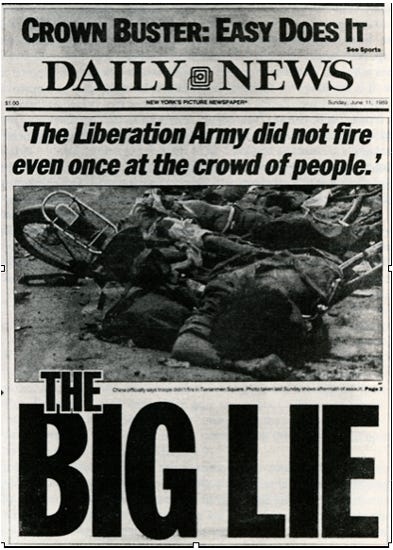

The fact that these videos were deemed by so many to have been factual and authentic is heartening, affirming that lens-based media can still at times be viewed as credible despite prevailing skepticism that has been exacerbated by the emergence of AI-generated imagery. It is reminiscent of when, in 1989, the Chinese government attempted to deny the massacre at Tiananmen Square but photographs were published that successfully refuted their attempt to rewrite history.

In 1990, when I was a guest the following year on The Today Show, a popular television program in the United States, Adobe introduced Photoshop to the American public when an employee inserted himself into a photograph of Ronald and Nancy Reagan waving as they stood in front of an American flag. I argued then on television that the software would make it much more difficult for photographic evidence to be utilized to stand up to governments, such as had been done concerning Tiananmen Square. Unfortunately, this has been the case. Now it tends to be videos made by amateurs that are more likely to serve as arbiters of events (including the one of George Floyd being murdered by police nearby in Minneapolis several years ago), their rawness eliding a generalized disillusionment about photography’s truthfulness.

Cautious viewers now require more of a narrative and contextualization, frequently aided as in this case by multiple perspectives as well as the emotional response of those nearby who were heard screaming in horror. The awkward framing from a distance also helps to establish the reality of the event — nothing seems posed or staged. It is increasingly the bystanders with whom we may more readily identify, imagining ourselves responding similarly as they do, rather than the more removed professionals.

That is why the video interview with David Guttenfelder is crucial; it allows us to identify with the human being who is witnessing and depicting events around him even as he works on assignment for the New York Times. The era of third-person “objective” photography in which we relied upon the camera as a mechanical observer is largely over; we need to know more than just what can be recorded in a fractional second.

Problematically, such photos and videos now must contend with an ever-growing amount of AI-generated images made by those who were not present. They undermine citizen journalism by producing fabricated imagery that, rather than contest governmental distortions, add to them. And, given the prevalence of AI, a viewer is then able to point to the synthetic imagery that seems to confirm their own point of view or reject the actual videos and photographs as possibly being tainted by AI or other manipulations.

It would be interesting if highly distressing to put together an AI-generated history of contemporary events under the Trump administration to see how far we have already veered from the real.

But on the positive side, galvanized perhaps in part by the horrified reception to the videos of Renee Good’s murder, there seems to be a growing energy that is apparent in the reporting of nationwide protests. Many of the photographs recently published do not simply show people holding signs as if only to establish their physical presence but begin to take them seriously as people who are enraged, terrified, and courageous. Their diversity and humanity, as well as their emerging power, is finally beginning to be understood as at least as important as the theatrical ICE raids that resemble the antics of a social media content creator, lacking any coherent purpose. The ICE agents begin to seem like the villains in comic books, violent and evil, while it is the anguish of the people being violently wrestled to the ground and arrested or killed, as well as those marching to defend them and their community, who are now being given more attention.

The photographs (below), some of those that were published recently in The New York Times in an article, Anti-ICE Protests Spread Nationwide, are more complex, especially when seen on a larger laptop screen, their framing allowing readers to peruse each one and interpret for themselves what is happening as with the videos of the Renee Good murder. Rather than providing simplistic answers, the photographers allow their imagery to be interrogated for meanings that are not pre-determined. These are not “point” pictures that merely establish that something happened while illustrating someone else’s text; they ask to be scrutinized by viewers who engage themselves in determining what they may represent.

Treating the viewer as sophisticated, as media literate, able to read an image and grapple with what it might convey, is how photography, whether it is journalistic or artistic, needs to be more frequently approached. A photograph should not be used exclusively to confirm events but needs to also be allowed its own at times ambiguous voice.

These photographs also provide the comforting certitude that one is not alone in anger or despair; there is a battle raging nationwide with an outcome that is far from pre-determined. Not only the performative cruelty of ICE agents needs to be witnessed and recorded, but also the enduring spirit of those who massively outnumber them and continue, both publicly and privately, to assert their own decency. We need to see more of them.

Please consider subscribing if at all possible as a paid subscriber. It would be deeply appreciated. As I hope is apparent, much work goes into each of these posts.

Exactly. Both photographers and readers need to be empowered.

Trust the viewers. I heartily agree, as assuredly as the sophistication of most has only increased as the signal-to-noise ratio has gotten worse. Thanks, Fred!