Covering the Protests

In a newsletter dated April 10, Kelly McBride, National Public Radio’s public editor who is also chair of the Craig Newmark Center for Ethics and Leadership at The Poynter Institute, wrote: “I was in New York City over the weekend. Knowing that I already had two letters about the lack of NPR’s coverage of protests in my inbox and that more would likely be coming, I went to watch the demonstration in Manhattan so I could judge the newsworthiness myself. As a news event, it wasn’t very compelling.”

There have been many complaints that the media in the United States is downplaying the massive protests occurring throughout the country against the conduct of the Trump administration. Social media is full of videos and photos of demonstrations, of people protesting against government policies in community forums and being aggressively hauled away by various security forces, but the mainstream media for the most part has been content to show groups of people holding signs without asking them who they are, why they are protesting, what it means for their specific communities, and so on. As news events, somehow these demonstrations were not, as McBride described the one she attended in Manhattan, “very compelling.”

That wasn’t always the case. During the Vietnam War similar protests were featured on front pages of newspapers. They did not have to become violent or unlawful for them to be considered important. See two examples below:

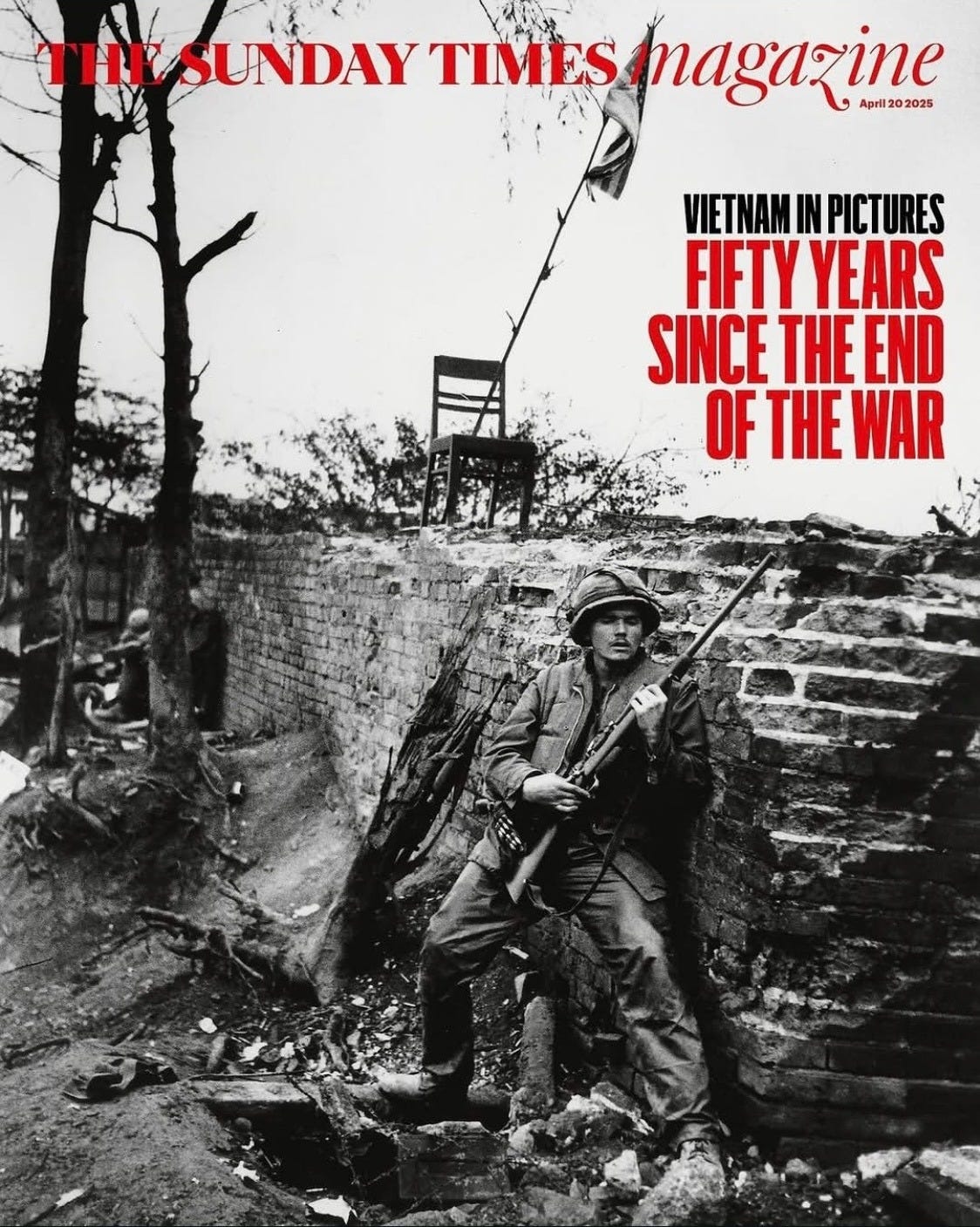

The fiftieth anniversary of the fall of Saigon, ending the Vietnam War, is this month, although so far there has been little mention of it in the US press. This past weekend the Sunday Times magazine in London published a vivid reminder on its cover, and highlighted the work of four British photographers who covered the war. These photographs, among many others, were pivotal in helping people abroad make up their minds about US government policy in Vietnam. The photographers, by showing what was actually happening at the ground level, often contradicted the high-minded declarations by military and political leaders of “pacification” and “winning the hearts and minds” of the Vietnamese people in what was said to be the pursuit of democracy.

Today, as well, photographers need to continue in the same vein, challenging the dictates of the current government and providing a grounded sense of the real in the face of so much distorting, disorienting rhetoric. It would also be important for media outlets to consistently highlight such imagery without simply repeating the clichés of people holding signs. Who are these people? What are they feeling? What do they want to happen? What is actually going on around us, and why?

Having attended this past weekend’s demonstration in New York City, standing in the middle of a crowd around the corner from what the photograph above shows, I can attest that it is deflating to see so little of what happened that day reflected in the media. It begins to make it seem as if, despite the thousands of people with whom I was marching through the middle of Manhattan, it was all a mirage.

PS: In the last AI Friday post — “The Photographic Moment” — auto-correct mistakenly modified the name of the World Press Photo global jury chair, Lucy Conticello. My apologies!

Please consider making a financial contribution to Notes of a MetaPhotographer.

One of the things to remember when comparing the 60's protests to now and media coverage, we had over 650 underground newspapers in almost every American city and college campus. The young protesters of that era had created their own media world as we did not trust the main stream media who were supporters of the war in Vietnam.We had the alternative Libration News Service, the AP of the underground media. The reach of the underground media was pretty massive. The Berkeley Barb at its height had over 100,000 readers for example. Maybe time to to back????