Before tackling some of the pressing images in AI-generated imagery, I wanted to return to my “Welcome” post from a month ago. Then I was critical of the widespread use, including many front pages, of the photograph of Donald Trump with his fist in the air after he had survived an assassination attempt. I wrote that “prioritizing the photograph of candidate Donald Trump defiantly holding up his fist after an assassination attempt, rather than the ones showing him shaken and needing to be supported by members of the Secret Service, certainly aided his election campaign. World Wrestling Entertainment could not have scripted it better and picture editors and others fell for it.” In the post I also presented an alternative front page of the New York Times using a photograph in which Trump looks vulnerable, requiring assistance from Secret Service agents.

Now, I’m happy to report, the jury for World Press Photo just selected a different photograph of the same event for its first-place award in the North and Central America “singles” category. They explain their reasoning for the alternative choice as being a “photograph [that] presents the main figure in a different light, providing a parallel narrative to the more performative moment which dominated press coverage…. and offers a glimpse into a moment that may have shaped the political landscape.” It is a welcome counterpoint to the fist-in-the-air photograph that journalist Piers Morgan immediately labeled as “…one of the most iconic photographs in American history—and one that I suspect will propel Donald Trump back to the White House.”

Photograph by Jabin Botsford for The Washington Post.

The initial decision that many took to depict “the more performative moment,” in the jury’s words, should be a cause for deep concern among visual journalists. The calculated gesture by Trump to project his own strength required contextualization as an example of Trump’s mastery of reality television, not as the reality of the moment. As Jason Farago would write in the New York Times, “The photos say, ‘I am safe; I am strong,’ but more powerfully they say, ‘I know I must look like I am safe; I know I must look like I am strong.’ The force of the photographs, in other words, rests not in what they depict politically, but what they convey about political depiction, which Mr. Trump seems to understand better than any other political figure of his day.… Mr. Trump had the instinct, amid mortal danger, to consider how everything would look.”

Similarly, AI-generated imagery allows one to create alternative universes that are less bound by the dictates of reality, as exemplified by two recent book projects by prominent members of the photographic community. Phillip Toledano’s We Are At War and Carl De Keyzer’s Putin’s Dream imagine situations both historical (the D-Day invasion during World War II as photographed by Robert Capa) and contemporary (Russian society under Vladimir Putin), without Toledano or De Keyzer having been there. While each of the authors makes it clear that their projects are not photographic but made with the assistance of artificial intelligence, they still provoke questions that are ethical, journalistic, and artistic.

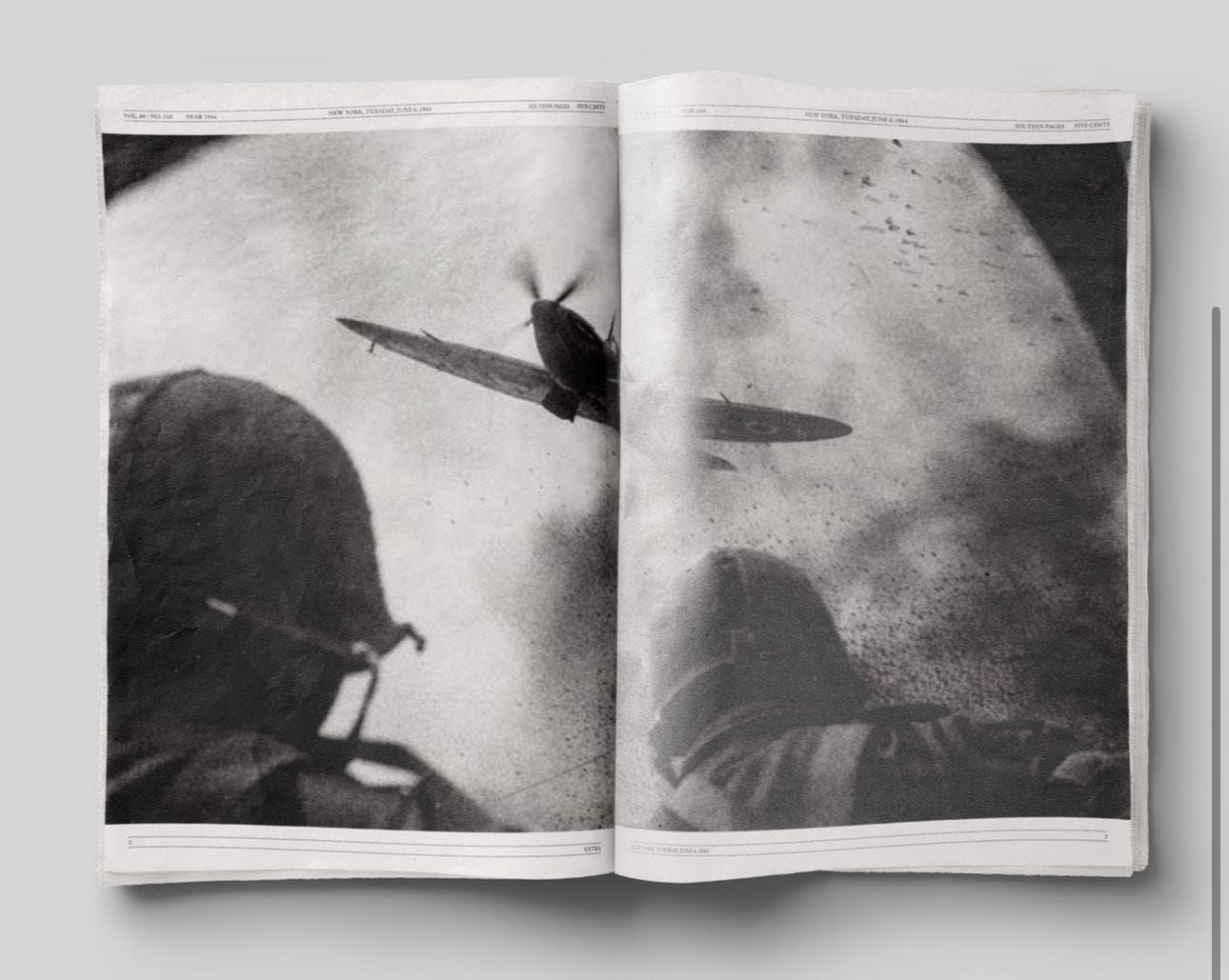

Capa photographed four rolls of film during the Normandy invasion but after a darkroom error only 11 images survived. “We Are At War is part of my continued exploration of historical surrealism - working with AI, I imagine one of Capa’s lost roll[s] of 36 images - and in doing so, demonstrate how utterly convincing invented history can be. If we can rewrite the past so persuasively, imagine what we can do with the present and even the future,” Toledano states.

“Now we’re in a reality where people just choose their history,” Toledano asserted in another interview, this one related to a previous project in which he used artificial intelligence to reimagine the United States of the 1940s and ’50s. “I think it’s an extraordinarily important point in history where we’ve come to the death of truth,” he told LensCulture. “Every lie can now have convincing evidence. And so that’s what this work is showing: look how convincingly we can create history that never happened with this technology. I think that as a species, as a society, we’re going to have to figure out a new way to understand what is true or what’s not. Or it may be that we’re entering a moment in history where we accept that there is no visual truth anymore.”

L-R, the cover of We Are At War and a “contact sheet” that accompanies the book. All of the images were generated by Philip Toledano with the help of artificial intelligence for We Are At War.

A spread from We Are At War.

Carl de Keyzer explores contemporary issues in Putin’s Dream. “In 2021, I wanted to start a new project about the new Russia under Putin. 20 years and 40 years after my last visits,” De Keyzer told PetaPixel. “COVID and the war prevented that. At first, I shelved the project but after a while thinking that AI might give me a chance to create the project in my head, I gave AI a try.” De Keyzer had previously published two books on Russia, Homo Sovieticus and ZONA, the latter on Siberian prison camps.

“I didn’t want to create a new style for this book. The images had to look like my photography, at least as much as possible,” he says in the same interview. “I can say I achieved that, my way of looking at the world as a photographer is in the book. That took more time than expected, AI can be tricky to train. But I see it as another tool to achieve new images and allow me to travel in my head.”

Inge Braeckman, in the introduction to the book that appears on De Keyzer’s website, concludes: “More specifically, art is a means of making the invisible real. And that is precisely what Carl De Keyzer does in Putin’s Dream,” A problem, even more so for a well-known documentary photographer, is that making “the invisible real” using photo-realistic AI may further confuse the viewer rather than help to clarify, while competing with the photographs made by those who are actually there.

All of the images above were generated by Carl De Keyzer with the help of Artificial Intelligence for Putin’s Dream.

De Keyzer is also a longtime member of Magnum Photos, the legendary agency widely respected for its chronicling of history since its founding in 1947. On November 14, 2024, the Magnum Board of Photographers issued, in response, the following statement:

“Magnum Photos respects and values the creative freedom of our photographers, supporting their diverse explorations and perspectives. However, our archive and distribution system will remain dedicated exclusively to photographic images taken by humans and that reflect real events and stories, in keeping with Magnum’s legacy and commitment to documentary tradition. Synthetic images will not be included in our archive.”

“Last year, in 2023, Magnum, as a cooperative, joined Writing With Light, a group of individuals and organizations that advocate for authenticity and credibility in nonfiction photography.

“Writing With Light is a movement to support nonfiction photography in which the integrity of the photographer, as the author of the image, is considered to be paramount in establishing the photograph’s veracity,” its website describes, in which “nonfiction photography” is defined as a “recording of the visible in which the photographer strives to represent actualities (events, people, etc.) in a fair and accurate manner with appropriate context.”

“In its Statement of Principles, Writing With Light covers three crucial rules:

1. As recordings of the visible, journalistic photographs must be fair and accurate representations of what the photographer witnessed.

2. Neither alterations to a photograph that mislead the public, nor staging events while depicting them as spontaneous, are acceptable in journalism. Nor should one publish a photorealistic synthetic image made by artificial intelligence and pretend that it is an actual photograph.

3. Any deviations to these basic principles must be explained in a caption, credit, or appropriate icon.”

The Magnum statement concludes: “For more information, please visit wwlight.org.”

(FYI, I am a founding member of Writing with Light.)

There is obviously much to consider in determining the value of such projects. Is it ethical to modify or speculatively add to an existing archive of photographs? When is it productive or problematic to produce realistic-looking AI-generated imagery of other countries, situations, or events? Are there times when the right to artistic freedom should override such considerations?

One can imagine many such scenarios. Individual practitioners, editors of publications, curators, historians, educators, and many others must proactively decide upon reasonable guidelines. This is an urgent societal conversation that these two projects should help to provoke.

More of my thoughts can be found in Vanity Fair where an excerpt from my new book was just published entitled, “In the Age of AI: Photography is Now Untethered.”

It would be greatly appreciated if you would become a paid subscriber. Your support will help me to devote more of my time to this critical turning point in visual media.

Interesting, the perspective that the "vulnerable" Trump is more authentic (or in AI-speak, not fake) than the "powerful" one. Both images are strong, both storytelling. Aren't both part of the narrative of the event?